4/3/22: The Political Is Sexual

The Eleventh Post.

Hey everyone. I have something a little more radical, a little more political than usual for you today. Once again I ask you to bear with me.

Is Everything Really About Sex?

Let me share one of the standard criticisms of Freud. The following was taken from this blog post by Scholar’s Stage:

The key to Freud’s success, I think, was not that he proposed human action was largely the product of unconscious perceptions, desires, and so forth. That was not new. What was new was Freud’s argument that all of these perceptions, desires, and complexes were the product of the sex drive. Freud changed the intellectual world by boiling human behavior down to sex. The unconscious was just a way stop on that path. It was a tool needed to explain away the incredible variety of emotions and impulses that make up human life.

Typically when I see critiques like this, I try to respond by denying the core claim, that Freud’s legacy was “boiling human behavior down to sex”. When the above post dropped, I wrote exactly that kind of response, the sort of response that Freud might assign to Reich’s work (as Reich did explicitly boil down human behavior to sex):

Another possible response would be to take Rorty’s angle in “Freud and Moral Reflection” and assign to Freud the notion of “quasi-persons”, which would eventually take shape in Eric Berne’s work (Parent, Adult, Child) and later in Internal Family Systems (IFS). Or you could take the angle Freud takes in Civilization and their Discontents, and discuss an innate drive to aggression as well as to sexuality, building on Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

Man’s “Wager”

But what if I didn’t refute the claim, and instead tried to affirm it, saying “yes, Freud did indeed boil down everything to sex”? This is what I’ve been thinking about in reference to a section from a Žižek paper I read a few weeks ago, “Otto Weinenger, or ‘Woman Doesn’t Exist’”, from his book The Metastases of Enjoyment. In particular, Žižek is trying to explain how Men and Women respectively respond to “the inconsistent surface of multiple masks”, for which the Lacanian name “is simply the subject”. In other words, how do we reconcile having multiple faces, multiple roles? For Žižek, men and women each treat this question differently, on a fundamental level.

I am primarily interested in how this inconsistency weighs on men in particular, and I’ve attached the paragraphs where Žižek discusses this below (p. 152-153):

I will quote the opening paragraph directly, because it’s most pertinent:

In the case of man, on the contrary [to women], the split is, as it were, externalized: man escapes the inconsistency of his desire by establishing a line of separation between the domain of the Phallus - that is, sexual enjoyment, the relationship with a sexual partner - and the non-Phallic - that is, the domain of ethical goals, of non-sexual 'public' activity (Exception). Here we encounter the paradox of 'states that are essentially by-products': man subordinates his relationship to a woman to the domain of ethical goals (forced to choose between woman and ethical duty - in the guise of professional obligation, etc. - he immediately opts for duty), yet he is simultaneously aware that only a relationship with a woman can bring him genuine 'happiness' or personal fulfilment. His 'wager' is that woman will be most effectively seduced precisely when he does not subordinate all his activity to her - what she will be unable to resist is her fascination with his 'public' activity - that is, her secret awareness that he is actually doing it for her.

What is Žižek saying here, in reading Lacan, who is reading Freud, if not that “all human behavior boils down to sex”? It’s not quite so simple: Žižek speaks of a “wager”, where the man takes up ethical goals, desexualized “masks” (like blogging), and acts them out dutifully, in the (typically not-conscious) hope that the quality of these non-sexual activities will be the thing that seduces a woman. And so sexual energy, libido, flows into non-sexual tasks, achieving some degree of “sublimation”, which was for Freud, the great achievement of civilization.

The key to this “achievement” is a sort of formal or logical linkage, by which the “wager” sustains itself: that there exists a conditional chain through which the man’s desire can ultimately be satisfied, so long as they perform their “duty” well. A total lack of such a structure results in auto-erotic behavior (i.e. the desire becomes turned toward oneself, one’s own body, rather than outward toward the Other).1 But what happens in the case of a severance, when the links in this chain, by which activities which were previously granted meaning through the “wager” become disconnected?

I asked this on Twitter and got a few pithy replies:

While I think these replies reveal something true, I want to dig into this question a little further, a little more broadly, to try and reveal not only what happens at the individual level but also at the societal level.

The Political Is Sexual

Curiously, I arrived at a similar formal structure over a year ago, when I wrote a thread about “the American Dream” that I never published, intended for my @simpolism account. It was perhaps overly cynical and overly optimistic. This is as good a time as any, so I’ll drop the thread here, in proto-Twitter form:

1/ I want to take the American Dream seriously for a second, as an aspect of American culture. But first -- what is a culture?

2/ In "Postmodern Condition", Lyotard writes: "[Social performances are] judged to be 'good' because they conform to the relevant criteria accepted in the social circle of the 'knower's' interlocutors. The early philosophers called this mode of legitimating statements 'opinion'.

3/ "The consensus that permits [knowledge of good performances] to be circumscribed and makes it possible to distinguish one who knows from one who doesn't (the foreigner, the child) is what constitutes the culture of a people."

4/ We can thus define the American Dream as a consensus, a set of opinions within American culture, about what constitutes a "good performance" of "living". But what is the American Dream concretely?

5/ As I see it, the American Dream is a "life path": perform academically, go to university, get a job, get married, buy a house (ideally in a nice neighborhood), have kids, raise them, retire, travel in your old age, and eventually die without making a fuss.

6/ More and more, the path within the American Dream seems untenable. You can't afford college. You hate your job. You can't find a partner. You can't afford a house, or kids. You can't afford to retire, or travel. Your death is slow and painful for you and those around you.

7/ Various systems support the American Dream. The university system. The economic system. The system of dating and courtship. The system of planning leading to the suburban living environment. The system of childcare. The pension and 401k systems. The healthcare system.

8/ Each of these systems now seems to be failing. And the first things to go are the connections between them, between each segment of the "path". Degrees no longer mean jobs. Jobs no longer mean enough money for a house. Marriage no longer means kids. And so forth.

9/ Ultimately the purpose of American culture, or really any culture, is to orient desire. As described earlier, the American Dream exists as knowledge of a consensus regarding life goals, instilled through family and media at a young age.

10/ What happens if the next "level" of desire becomes unattainable, you can't find a job, a wife, a house? Frustration. Which acts upon each person in different ways.

11/ For one, frustration may lead to anxiety as the goals recede, lack of desire once it fades. For another, it may lead to distractedness, an inability to retain focus, as each desire is partially but not fully satisfied. Why invest oneself if achievement remains out of reach?

12/ The final response to frustration is to give up. Release the desire and reorient, create a new desire. Destroy the dream, start new. But that also means giving up the Plan. And this leaves behind a void. Why do you think everyone is depressed these days?

13/ This loss of the Plan raises the question of "who am I now? And what shall I do?", and many respond by attaching themselves to ideologies which possess the image of a replacement. Hence the resurgence of religion among people, especially young.

14/ Certain ideologies even "bounce off" the lost American Dream, proclaiming themselves as its inheritors. You see this on the left, with social justice, and on the right, with its renewed ethnic nationalism.

15/ Neoliberal technocracy, however, remains the true heir to the American Dream, promising a meritocratic continuation of the "standard" life paths.

16/ Yet the fruits of Neoliberalism remain out of reach to the majority, both for economic reasons and moral ones, international media vastly increasing awareness of "who loses at my expense?".

17/ What's one to do? Tradition works well in times of stability or plenty. And that's exactly what we lack right now. IMO, the best choice for a volatile era is to cultivate knowledge and flexibility, the ability to bounce back regardless of what Life throws at you.

18/ I think many today are working to develop this sort of flexibility. We're seeing a new renaissance of critique and thought, attempting to provide new tools for navigating stormier seas.

Fin/ But I think we, especially us Millennials, will be forever haunted by the fantasy of an earlier era, when life was simply easier. The challenge will be learning to take the difficulties of our present era in stride, and avoid falling into despair over that "lost" fantasy.

If Žižek claimed that “The Sexual Is Political”, then the synthesis of the above implies the converse is true as well, that “The Political Is Sexual”: institutional bodies, controlled by way of political decision-making, are systems that mediate our capacity to fulfill our sexual, romantic, intimate needs, and are fundamentally “by-products” of that basic, phallic desire. The incel movement makes this very clear: what else is a “state-mandated gf” if not just a compression and condensation of the ultimate aims of a specific bloc, the “failsons” who cannot stomach the “wager” any longer?

Lacan himself expresses a similar sentiment himself, with subtler language, in a little passage I’ve been interested in since I first started studying the guy (Seminar XX, p. 3):

A word here to shed light on the relationship between law [droit, rights] and jouissance. “Usufruct” — that’s a legal notion, isn’t it? — brings together in one word what I already mentioned in my seminar on ethics, namely, the difference between utility [l’utile, the useful] and jouissance. What purpose does utility serve? That has never been well defined owing to the prodigious respect speaking beings have, due to language, for means. “Usufruct” means that you can enjoy [jouir de, take advantage of, get off on] your means, but must not waste them. When you have the usufruct of an inheritance, you can enjoy the inheritance [en jouir] as long as you don’t use up too much of it. That is clearly the essence of law — to divide up, distribute, or reattribute everything that counts as jouissance.

What is jouissance? Here it amounts to no more than a negative instance [instance, insistence]. Jouissance is what serves no purpose [ne sert à rien] [i.e. sex, a “purposeless” activity we do simply “for fun”].

In other words, the essence of law, itself the result of politics, is “to divide up, distribute, or reattribute everything that counts as jouissance”. The back and forth of left and right politics can be seen simply as each party’s attempt to capture more of this enjoyment for themselves, by excluding outsiders or enabling their constituency to better pursue their aims, whether directly (e.g. abortion law) or indirectly (by assenting and supporting certain “wagers”, like science, academia, manufacturing, etc.). The voting power is split about evenly between parties, so back and forth it goes.

Dating, Apps, and Politics

Default Friend, in a recent article, conceives of a different axis where we might see a more broad-scale, unified political movement. Echoing back to my not-quite-Tweet-thread’s idea that “Neoliberal technocracy, however, remains the true heir to the American Dream, promising a meritocratic continuation of the ‘standard’ life paths”, DF identifies pro-tech vs anti-tech as a fault line with potential for a mass movement. But why? She writes:

There is a reason why a broad tech backlash has not yet materialized. If you look at all the anti-tech blips of the last two decades, not enough has been at stake. Maybe to ideologues, sure, but not to the everyman. We are all familiar with the ways in which tech has made us less educated, less connected, less free, and less healthy, but there is no united front against tech as a whole. One man’s atomization is another man’s convenience.

There’s one exception to this: sex.

…

When it comes to relationships, technological progress has not led to better outcomes. In 2020, most singles in the United States reported being dissatisfied with their dating lives, 67 percent of people think their dating lives “aren’t going well at all,” and 47 percent of them say it’s harder to date today than it was 10 years ago. The share of adults ages 25 to 54 living without a spouse or partner has risen 29 percent since 1990. Americans are having fewer children. Women are not only marrying later, many are not marrying at all. We are in the midst of a sex recession that may be turning into a “Sex Great Depression.”Many of these trends go back much further than dating apps, but the failure of dating apps to deliver on their promises calls into question the broader ideology of progress and cult of technology.

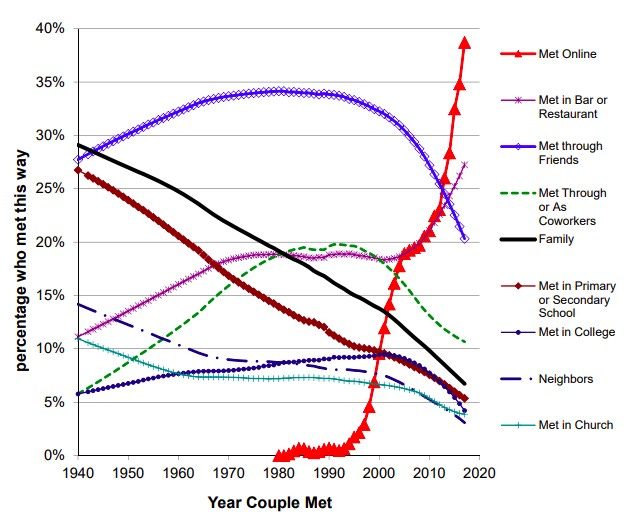

Taking a brief glance at the statistics below, it looks a lot like dating apps represent the current “key link” that permits the sexual “wager” to continue making sense. In other words, the “wager” more and more only “works” to the extent that dating apps result in actual relationships. And this is seeming less and less true as more and more people try the apps, and fail.

Of course, the “normal” user’s failure is intentional on the part of the dating apps. They want you to fail just closely enough that they can keep making money. But, more broadly speaking, the “desocialization” and “desexualization” of life could have disastrous consequences in terms of the average person’s desire to continue, well, working, and generally taking duty upon themselves.

This shift is already becoming visible on places like Reddit’s /r/antiwork, where users revel in the meaningnessless of jobs and wealth, as well as the growing antipathy toward tech from “culture” publications. In a somewhat less PC vein, noting also that all of the above is in reference to men’s way of reconciling “the inconsistency of his desire”, what might we expect to see except… fewer people wanting to be men2 I don’t intend to speak for all trans people here, or even any trans people, but is it not the case that becoming not-a-man is a way of solving the problem of the failed sexual wager, by denying it entirely, and taking a different route toward reconciliation? And is this not the very same shift motivating the “alt-right”, who seek to reestablish the potential success of the wager by retvrning to prior institutions that once enacted it? (PUA/TRP notwithstanding, who take it upon themselves to make the current situation work, by any means necessary, and thus serve a very important function in terms of dating app marketing.)

A major aspect of the “problem” with dating apps is the “shallowness” of the wager. I recently expressed to a friend that “I feel like everyone on dating apps is a eugenicist, myself included”. In other words, the apps only make the barest attempt to hide the phallic core of desire. A man’s only means for demonstrating the strength of his “wager” on Tinder, at least, is 6-9 photos and 500 characters of text, which can only express the shallowest sort of commitment to any sort of ethical goal or duty beyond oneself. There is little potential for the “melodrama” Žižek refers to, of making the ultimate sacrifice for love. He makes this point himself in a video from a few years ago, in a less technical form, about how online dating precludes the “fall” of love:

Sexbots and Technopolitics

If Default Friend’s wager is right, we may end up seeing a backlash against technological intervention, plausibly stemming from the failure of dating apps to satisfy us, to make us happy. But what if she’s wrong? Isabel Millar, whose book The Psychoanalysis of Artificial Intelligence I wrote briefly about earlier, believes the answer might be “sexbots”. She writes (p. 151):

According to the apocalyptic fears of the likes of Richardson (2018) a Westworld scenario could become reality. Capitalism would facilitate that the sex robot industry grows exponentially, unfettered by economic, ethical or legal restrictions, eventually society would fully embrace the possibility of access to sex robots for all a la Westworld. Furthermore, if, following the young Nick Land (2011), we conceptualize capitalism and Artificial Intelligence as one in the same thing—i.e. as capitalism itself being a form of autonomous intelligent life—then given free rein, we would quickly achieve optimal conditions for the most sophisticated development of artificially intelligent fully functional sex robots.

Millar then goes on to ask ethical questions about the potential status of sexbots in this future world, which I don’t have time to explore in any real detail. But in comparing sexbots to Marquis de Sade’s libertine philosophy, she makes the following point (p. 157-158):

…the libertines when all is said and done, can never achieve the full satisfaction they desire because it is always thwarted by the very human cycles of excitement and orgasm that are ultimately and inevitably always returning back to a state of equilibrium. So, could we not say that the ultimate pleasure for the libertine is in fact not just death, but immortality, to be the undead. Te paradox for the libertines is that their bodily existence is both a source of unbounded enjoyment and also a barrier to the (fantasized) full and complete enjoyment of the ‘beyond death’. As subjects of the symbolic or speaking bodies, the libertines can never really reach this state of plenitude and will always be subjected to the cycles of human pleasure, pain and eventually death. In which case perhaps the libertine would not wish to have a Sexbot, but to be one?

Does this not contain of the other side of DF’s fault-line? Echoes of the rationalist, techno-optimist fantasy, of mind-uploading immortality, to a realm of eternal enjoyment, the transhumanist “mind-blowing orgy of erotic existence” (Millar, p. 115), only possible for a sort of “undead” being?

Millar’s reference to Sade comes from Lacan’s paper “Kant avec Sade”. So it is ironic that this divide, pro-tech vs anti-tech, comes to mirror the moral divide of the 18th and 19th centuries, as articulated by Charles Taylor (A Secular Age, p. 288), in relation to Kant and Hume:

[Morality, the law which binds us,] will often be seen as revealed to us by Reason, following a study of reality, or else of the very structure of Reason itself. But to the extent that disengagement is seen as essential to Reason, then the body tends to fall away. So we gravitate towards two possible positions; one tells us that we have to factor out our embodied feeling, our “gut reactions” in determining what is right, even set aside our desires and emotions. This move finds a paradigm statement in the work of Kant. Or else, we turn against the excessive claims of reason, and base morality on emotions, as we find with Hume. But just for that reason we undercut the aura of the higher that usually surrounds these feelings, giving them a purely naturalistic explanation. Embodied feeling is no longer a medium in which we relate to what we recognize as rightly bearing an aura of the higher; either we do recognize something like this, and we see reason as our unique access to it; or we tend to reject this kind of higher altogether, reducing it through naturalistic explanation.

Lacan and Millar’s maneuver becomes clearer here: the absolute limit of Kantian moral law (read: pro-tech) is a sort of absolute, God-like libertinism, brought about through rational means that disregard our “gut feelings” (i.e. we must go beyond our emotions in order to truly transcend to the Heavenly realm of pleasure). On the other side, by basing moral decision-making on emotions and gut feelings, as with Hume (read: anti-tech), one might ironically end up undercutting the transcendent or higher nature of sex, i.e. precisely the thing that makes it seem valuable to us.

Does this not call back to the issue presented in the original Žižek quote I shared, whereby phallic desire must not be expressed directly in order for it to reach its most sublime expression? Similarly, any movement that bases itself explicitly on sex-qua-tech has the potential to undercut its own goals. But might we see a sort of “political sublimation”, where dissatisfaction with dating apps intensifies and pours out into a broader, more ethically-oriented anti-tech sentiment, one as not-so-secretly rooted in the failure of the “wager” as the “wager” is itself not-so-secretly rooted in sex?

I can’t predict the future, all I can do is draw some outlines, point to a couple of paths. Remember that the entire analysis above is rooted in the quasi-Freudian idea that, at the end of the day, it’s all about sex. Ultimately, we may find that day is instead ruled by self-preservation, aggression, the ego, and that none of the above comes to pass, that we instead expend our energy dealing with natural and artificial disasters, wars and climate change. I’ll leave the analysis of that side to other, more geopolitically-savvy writers, like the one I mentioned all the way at the beginning, Scholar’s Stage.

Miscellania

Phew, another long one. Thanks for once again sticking with me! Now for a couple unrelated notes.

Here’s an app that lets you talk to yourself:

Some naive thoughts on climate change and politics (thread):

Song of the week:

Auto-erotism as such is the original meaning of the term “autism”. And, as expected, there are more autists now than ever before.

Note that I did not discuss the way that women might attempt to reconcile this same inconsistency, but suffice to say that they don’t fare much better as far as satisfaction is concerned, although perhaps for somewhat different reasons.