I. Intro & tl;dr

If you prefer audio, my friend made a NotebookLM podcast version of this post that's actually pretty good. Grab it here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/13shr-pXSt0cx_4kGb0S8vIr5VSODFefL/view?usp=drivesdk

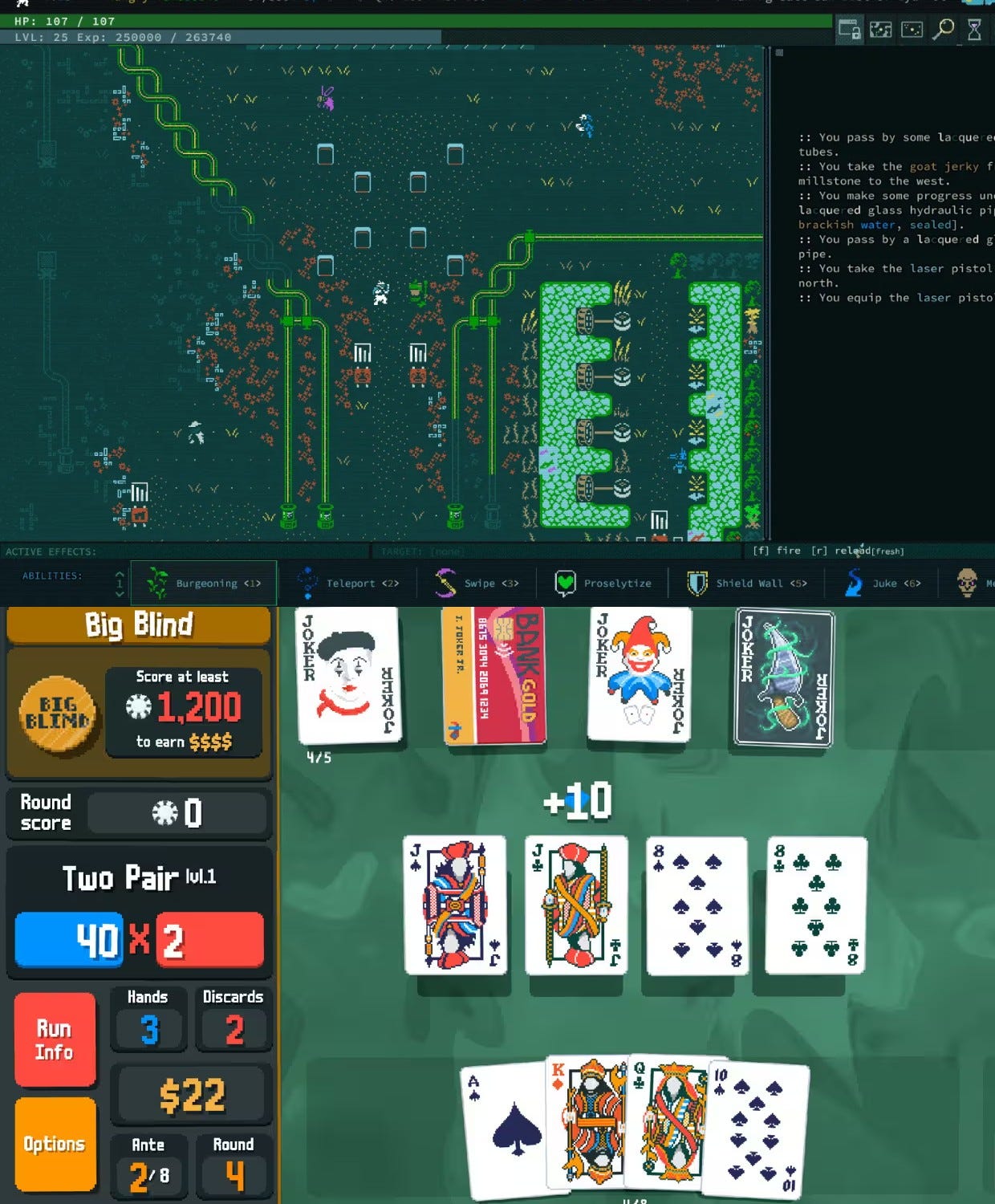

Yesterday, a viral image started making the rounds:

One of the responses was from tautologer, who claimed that Balatro is not art. I argued it definitely is art, pulling on the idea that video games are a craft based on choice via mechanism design, which is an idea I’ve explored previously on this blog (vis-a-vis Keith Burgun’s Clockwork Game Design and Frank Lantz’s The Beauty of Games), and arguing (loosely based on Sloterdijk’s You Must Change Your Life) that a craft + a shared hierarchy of value judgment is sufficient to determine an artform. Balatro’s mechanisms are decidedly well crafted, therefore Balatro is art. One and done.

And yet, based on the image above, Balatro elevates few of the forms that the image creator believes “should” define video games as art: visual depictions, music, writing. As with the emergence of photography as an art, my position is that it only makes sense to evaluate video games on the basis of their unique qualities as media, which in this case is the small “+ interactivity”, rather than what they share with other media. You can use photographs to render realism “better” than paintings, but photography wasn’t “really art” until communities of practice and judgment began to approach it as its own unique thing, not just a mechanical echo of painting.

Video games come in diverse forms, with diverse communities of creation judgment, and thus there’s many different ways for video games to be art. I want to use this post to explore the evolution of a few lineages that I personally find compelling— Roguelikes and RPGs— from the perspective of art, in particular the idea of modernism, leaving the terrain open for intrepid FPS and Platformer gamers to draw their own narratives.

II. Roguelikes as Systems Art

What is a Roguelike? What does Balatro, which looks like a card game, have to do with Rogue, a top-down dungeon crawler from 1980?

Much has already been written about what a Roguelike is or isn’t (this is a fun piece for those with some familiarity already). Rather than trying for an essential definition, I’m going to simply highlight the commonalities:

The basic conceptual loop of a roguelike is to become more powerful through skillful composition of items.

The basic goal of a roguelike is to finish a single run, or get as far as you can, which is the reason for becoming powerful. Typically you cannot set checkpoints in runs: you either finish it and win, or lose and have to start completely over.

Item selection involves randomization: you can’t just pick what you want, you need to do your best with what the game offers you.

Composition of items takes the form of combos, where item effects combine to produce an effect more powerful than each single item on its own.

To form powerful combos in the face of randomization, you must gain mechanical knowledge of the game’s systems, that allows you to make good choices at each decision point, typically with regard to what items you want to use or skip.

The craft of the roguelike designer is to come up with mechanical systems that are sufficiently balanced as so to feel at least somewhat fair (although “breaking the game” through overpowered combos is often possible and even encouraged), and, more importantly, to ensure the systems are sufficiently complex to permit a lot of emergent behavior, which is the essential building block of the combo. “Complex” in this sense means the functioning of each mechanical element is deeply entwined with the other elements: the “gears” of the mechanisms all connect to each other in not-immediately-obvious ways.

Let’s look at some games to better illustrate what these points mean. I haven’t spent a lot of time with Rogue, but I’ve played a lot of Caves of Qud lately, which is a mechanically traditional Roguelike (top down, on a grid, randomly-generated dungeon crawling) with some RPG elements (i.e. a quest-line that’s available every play, a leveling system).

Ignoring the RPG elements, the “point” of Caves of Qud is to set up configurations of items through knowledge of the mechanics that lets you beat or escape from more and more powerful monsters. You can get randomly generated powerful items (relics) by finishing one of the random dungeons.

As a simple example: let’s say you finish a dungeon crawl and get a relic that gives you Electrical Generation. That means you’re now generating power. You can then use your Tinkering skill to make items “Jacked”, which means they draw from your personal electrical generation rather than from a battery. Apply “Jacked” to a Force Bracelet, which creates forcefields but draws a lot of power, and now you can have infinite force fields and basically nothing on the map can touch you, so you can explore as you please. Of course, there’s still ways for certain things to kill you even with an infinite force field, but you’ve just gotten a whole lot more survivable, and survivability is key to finishing a run successfully.

These classic roguelikes, where you dive into dungeons in search of rare gear to equip, are the “traditional” form of the game. They have all the hallmarks of Rogue, grids and turn-based movement, an equipment system and consumable system, random generation of space, knowledge of combos, etc. It’s a great template that’s lasted 40 years and is still fun to play.

But, enterprising game developers who looked closely at traditional roguelikes, in particular at what makes them “fun”, discovered that much of the fun isn’t in the dungeon crawling itself, but in the combos and randomness. It’s as if the dungeon crawling was a form of “labor” the player had to do to experience the “fun” of getting stronger, akin to the “labor” of realistic depiction in painting that might not even be necessary for the enjoyment of color and form.

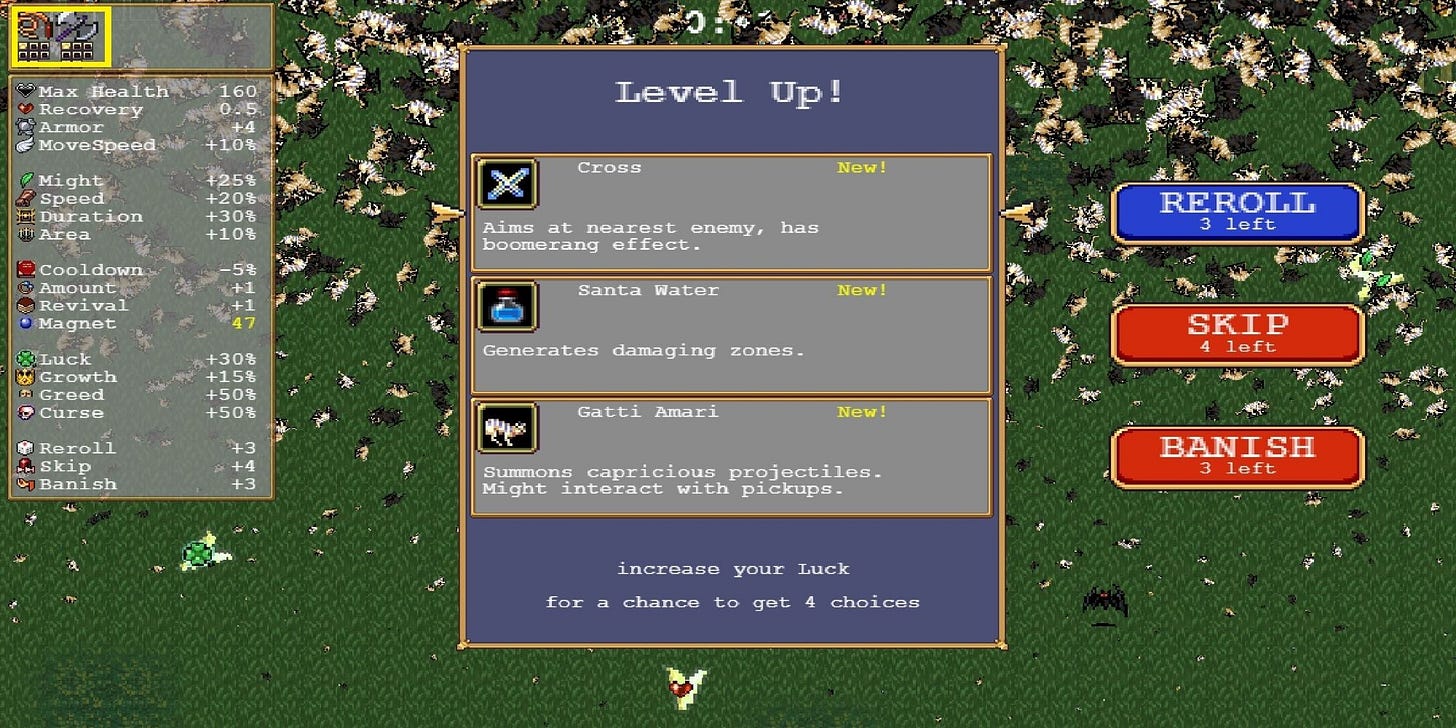

As an intermediate example, consider a game I previously wrote about, Vampire Survivors. In Vampire Survivors, the combat happens “automatically” (and even “traditional” roguelikes like Caves of Qud have an “autoexplore” feature that’s similar). So, you do a little bit of labor by running around, especially early in the game, and eventually the entire game becomes “steering” the processes, i.e. combos, that you set up through your item selection. Each round lasts a flat 30 minutes, so all you need to do is survive.

Randomized item choice in Vampire Survivors happens through upgrade selection when you level up:

This is where you need to think carefully about what item you’ll take, to set up combos that will power you through the late game.

But what if we remove time and space entirely, leaving only item selection and power? Is that not akin to removing any kind of realistic representation in a painting, leaving only form and color?

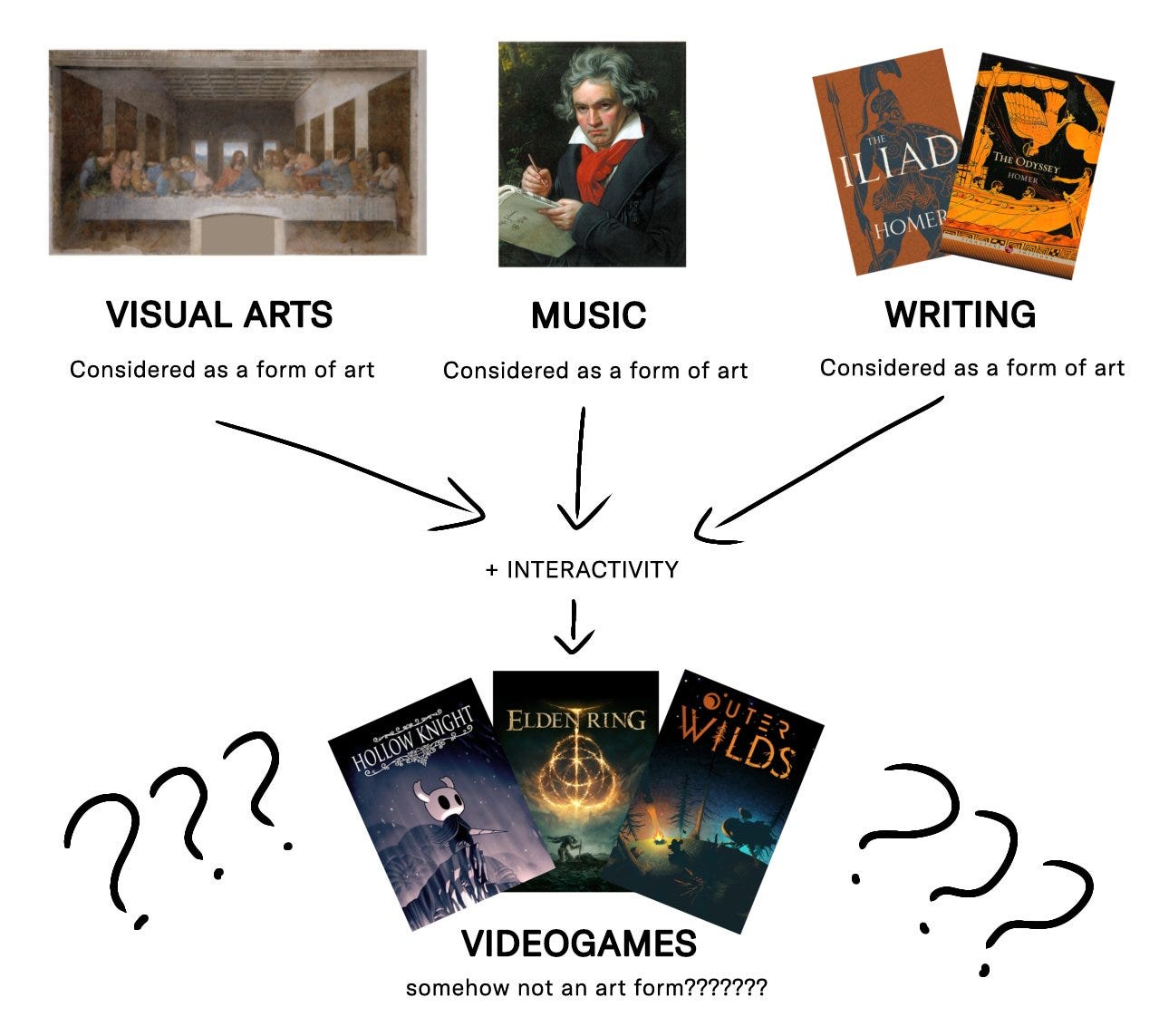

This is what Balatro does. A significant portion of the game revolves around the Shop, where you pick Jokers, forming the raw material for your combos and strategy, as well as Vouchers, which are permanent upgrades, and Packs, which can give you a choice of random consumables or cards for your deck. It’s pure resource management.

The gameplay is then a poker-like system of playing card tricks for points, and trying to make sure you get enough points to beat the round goal. The better you do, the more cash you earn for the next shop. No more time and space, only alternating sequences of configuration and execution, form and color, without any attempt at “simulating” some kind of dungeon crawling experience.

Balatro, in its massive success, has distilled a set of “fun” elements of the Roguelike, specifically relating to mechanism and power, into a simple form that preserves the complexity without the “bloat” of the other, more labor-intensive aspects of gameplay. Prior to Balatro, a lot of roguelikes relied on combining the mechanism design with other types of gameplay, like how Caves of Qud has a world map and quest line like an RPG, and The Binding of Isaac has a bullet hell reflex component as well as the roguelike randomness and item shop.

But can we take it further? What comes after the pure abstraction of the roguelike as mechanism? A game that came out in March, called Nubby’s Number Factory, gives us a hint.

Nubby’s Number Factory has many elements in common with Balatro (shop and boss loops, comboing, etc), except you’re shooting a pachinko ball rather than playing cards, and it has a Windows 95 aesthetic rather than pixel art. But a few specific and hilarious choices add a self-referential edge:

The game setting is a number factory where your job is explicitly to “make number go up”. “Number go up” is commonly joked about as the “point” of modern roguelike games (and in Vampire Survivors, the numbers get visually larger as they go up, adding some “juice” to the game).

The “boss” of the number factory, the person who wants you to make number go up, is an animated image of the game designer himself, “Tony”.

In other words, the game is making fun of your awareness that you’re playing a game, while also being a good game. Have we not moved into a kind of postmodern roguelike territory, adding a reflexivity on top of the purely formalist construction of Balatro? Like a painting where you’re supposed to see the brush strokes explicitly, drawing attention to the fact that it is ultimately a painting, even as you recognize the way it wields form and color as the modernists did.

III. RPGs as Narrative Art

Although it deserves just as much time, I want to run through some history of Role-Playing Games (RPGs), with an emphasis on Japanese RPGs (JRPGs), and show a similar progression taking place. As opposed to the more “visual” systems games, JRPGs are narrative games, and draw closer analogies to literature rather than painting.

You can think of classic JRPGs like Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy and even Pokémon as being closer to the classical novel, where the idea is to enjoy the activities of a protagonist, with the distinctions that (a) you “control” the protagonist’s actions in the JRPG, and (b) you need to perform a lot of labor— fighting, doing mechanical things, etc.— as part of the experience. Most of the “fun” is in following the story while feeling like “you” are really the one doing the work to move it forward, even though most JRPGs are entirely on rails, i.e. have no meaningful decisions throughout the game.

The original Dragon Quest was the worst offender here. A lot of the game is just… grinding, i.e. doing battle sequences over and over again to get experience and money so you can get stronger and do stronger battles, until you’re strong enough to rescue the princess or whatever.

Many of these decisions were intentional on the part of Dragon Quest’s designers. It was supposed to be a relaxed console game in a day when gaming was serious and PC-dominated. As Yuji Horii, developer of the series, says in an interview:

For the Dragon Quest series, control itself is not the main focus of the games. When we design the game, it's just like driving a car. When you're driving a car, you don't really get concerned about how you control the car itself; you just enjoy the drive. You know how to drive it without thinking about it -- that's what we're trying to do.

In other words, JRPGs began as “casual” games. This choice sits in an uneasy tension with great art that aims to bring something “higher” into being.

Some RPGs, especially the early ones, included a lot of additional mechanics, like Rainbow Silkroad’s mercantilism, which I wrote about previously, solving puzzles, and, of course, dungeon crawling. But let’s just say: dungeons are a lot less stressful when death doesn’t mean starting over entirely.

In general, we can claim that RPGs end up either as walking simulators (i.e. narrative adventures), or as grinding simulators (i.e. a form of systematized labor where you get stronger by dumping more time into it, without the element of knowledge required to advance in roguelikes).

RPGs started getting weird and self-referential very quickly, likely due to their popularity and tight constraints on design. Earthbound came out less than 10 years after Dragon Quest, and already enjoyed deconstructing the tropes of these games. However, in many ways, it was very much the same form of game as the others, just with a fun aesthetic twist.

But then, after going 3D in the mid 90s with the release of the PlayStation, RPGs seemed to lose that intellectual or self-referential edge, at least until the last decade, with a few strange exceptions (or maybe I’m just not aware of the experimental 3D-era RPGs). One such exception is Yume Nikki, a true “walking simulator” by an anonymous Japanese developer where you wander through a dream enjoying the surreal landscapes. It strips away everything: narrative, battle, most puzzle, in favor of pure… walking, freely, through the world.

The next highlight for RPG-as-art comes right at the beginning of the indie development era, with thecatamites’ Space Funeral. Formally, it has the same features as all the mainline JRPGs, but had a quirky art style and sought to make fun of many of the big games’ tropes, such as by having absurdly easy battles and nonsense storylines. It’s also so short you can play it in one sitting, and free (try it).

In my opinion, CrossCode was the first game to really break out from the basic JRPG template. I don’t want to give away spoilers, but the setting of the game is that you’re playing an MMORPG (e.g. World of Warcraft), giving it a self-referential frame off the bat. Like the games above, it jokes with the conventions of RPG gaming while still being an RPG with as epic a narrative and great environments as any of them.

That said, most of the game is still… puzzles and grinding, but it’s a little funnier from the framing that it’s all “fake”, i.e. part of a game (inside the actual game). This coincides with the popularity of the Isekai anime genre, which is, anime set inside a virtual world. The cultural theme of the blurring lines of real vs game has taken root in games themselves.

CrossCode inspired another game that I think is most interesting of the bunch conceptually. Rather than a walking simulator, what if we made a grinding simulator? Enter: Secrets of Grindea, a game where the entire point of the plot is… grinding. It pulls a lot of the real-time mechanics from CrossCode and earlier SNES games like Secret of Mana, but the entire plot of the game is a surreal adventure involving the secret art of grinding (i.e. fighting hordes of enemies for long periods trying to get rare loot).

Frankly, I still feel RPGs have a long way to go, creatively speaking, which begins with solving the issue of “false choice” as I discuss in my older post on the topic. The games still can’t figure out if they’re Walking Simulators, Grinding Simulators, or Visual Novels, and that makes them difficult to evaluate. I haven’t yet played a RPG that manages to synthesize these aspects in a way that transcends them, or is greater than the sum of their parts. Some specific moments get close, like the first sequence in Dragon Quest 5 when you emerge onto the bow of a ship as a child with grand adventure music playing, but film is a far better medium for this kind of elevated moment.

Maybe this is a limitation of my personal psychology, maybe I haven’t played the right ones, but my assessment of the RPG form as it stands is that it’s closer to genre fiction, where you can have “local” great works and find writers like Borges toying with the conventions, but at the end of the day, any true masterpieces end up breaking out of the template entirely.

However, since what most “casual” gamers are familiar with are RPGs, often through early experiences with Pokémon, I feel that most people have poor expectations about the artistic value of video games in general. Perhaps the image all the way at the top questioning whether video games are art is based on the RPG, which in many cases really aren’t much more than visual arts + music + writing + interactivity.

We can more easily find great works if we look at games which work with a smaller, tighter subset of RPG mechanisms, such as YU-NO: A Girl Who Chants Love at the Bound of this World, an erotic visual novel for the PC-98 (a Japanese computer) that wielded its writing, graphics, music1, and time-travel-based point-and-click gameplay to far greater effect than any JRPG I’ve played, at the expense of… “full” (i.e. grid-based) interactivity? Worth it, for the art.

Give me this autistic ramble on the music of YU-NO (put it on and take a deep breath and listen to the first few tracks!!!). It was composed by Ryu Umemoto when he was 21 years old: the guy was a savant of the FM synthesizer chip. He died in his 30s. Just stopped breathing one night and never woke up. There’s over 5 hours of music in the game, and some of it is absolutely incredible, pushing the hardware to its limits. He invented a series of scales referencing Zen Buddhism concepts to structure the pieces. It’s just brilliant, especially compared to the mass of FM garbage people were composing for the Sega Genesis around that time, with the possible exception of Alien Soldier. The game itself is massively elevated due to his music.

Yep, we have magic and miracles for 70+ since the creating of video games. We can build a whole direct democratic simulated multiverse and solve AI safety. No kidding, we shared the full proposal with UIs and more

The reason videogames aren’t art is because they’re not produced by the Art World and don’t engage with Art History (i.e. the history of the Art World). But this is a good thing.